UPDATE: We’ve posted a public statement about this post here.

Hello there.

Way back in December we posted an update saying that we would post “about our terrible IGF experience.” Granted, we may have exaggerated a few things back then. (read: a lot of things!) But with the IGF finals at GDC coming up, there is no better time than the present to relate our experience.

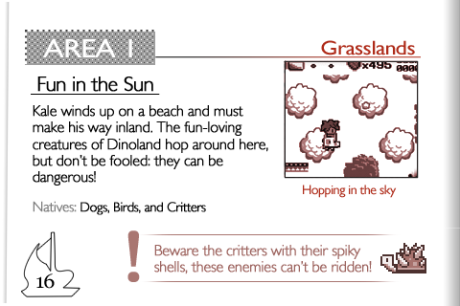

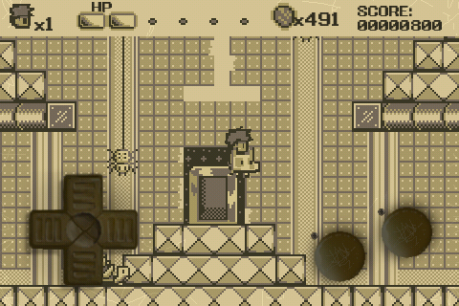

First, some backstory: We are an independent developer producing an iPhone game named Kale In Dinoland:

This year the IGF decided to use TestFlight for its iPhone games. We paid the $100 customary to the festival, as over 500 other developers did for their games. Going in, we didn’t expect to get nominated for anything. The game was content-complete but wasn’t done to the level of polish we wanted. Not to mention, there were still bugs. But this isn’t about the overall quality of our build, it’s about giving every game its fair shake.

Let me explain. When the IGF chose TestFlight for iOS distribution, they made a big mistake. We were given a list of all of our judges’ email addresses, revealing their identities. We aren’t going to release those names to respect the judges, but let’s just say we had a heavy-hitter. For every judge, we could see how much they played; if they even started the game at all. How do we know this?

TestFlight records NSLogs (iPhone version of console logging) and custom “checkpoints,” uploading this data seamlessly for us to see. In addition, when a judge opened the TestFlight invitation email, downloaded and then installed the game on their iDevice, we can see all of that. I believe that the IGF organizers, who are usually lips-sealed on the judging process, did not know about this functionality. We can see exactly when a judge installed the game, when they started playing, how long they played, and how far they got.

As you can imagine, this was an opportunity for us to see what really goes on behind closed doors at the IGF. How much do games really get played? Does hype count for everything? Is it true that to be a contender in the current IGF, your game has to already be widely known in indie circles? Does this mean that most of the judges won’t end up playing your game in these circumstances regardless of the quality of the title?

Here are the statistics:

Eight (8) judges were assigned to Kale In Dinoland. Of those judges, 1 didn’t install the game or respond to any of our invitations (which we had to send multiple times before judges joined). 3 judges didn’t play the game. Of the remaining 5 judges that played the game, 3 played it very close to the IGF deadline, which was December 5th. One judge, our outlier, played the game for 53.2 minutes. Excluding the outlier, on average each judge – including the 3 that didn’t play it – played the game for almost 5 minutes’ time. Back in that build, Kale’s intro cutscene took about a minute’s time. So we’re talking almost 4 minutes for each judge of actual game time.

Granted, they could have deduced the game was absolutely terrible and didn’t deserve their time. About this time, though, we were also running a beta that was being played by anonymous iOS gamers from the community. These helpful gamers were all interested in the game, having seen it on TouchArcade and IndieGames.com. What is the influence of prior marketing? The average play time for these external beta testers was 34 minutes, accounting for that one minute of cutscene time.

So, a large group of anonymous gamers who were not required to play the game averaged about 30 minutes more play time than the the 7 judges who were required to play the game, 3 of whom did not even play the game. Is 4 minutes enough time for someone to give a fair assessment of a 2-hour-long game? How many more games were given similar treatment? Had we not taken initiative and sent multiple emails urging judges to download the game via TestFlight, how many judges would have ended up playing the game? Here’s the last email I sent out, urging the judges to accept the TF invite:

The build has been up for a while now (I sent emails via TF), but only 1 judge has installed, and 4 other judges still haven’t even signed up for TestFlight.

The sad truth is, the heads of the IGF know about all of this. They made the mistake of using TestFlight and allowing us, the developers, to see backstage. Shortly after posting the update that included negative remarks about the IGF – on this relatively unknown blog – we were mysteriously followed on Twitter by @brandonnn and received an email from none other than Simon Carless.

Hey folks,

It’s just been brought to my attention that you believe that you’ve had some issues with your IGF experience and are preparing to blog about it. My name’s Simon Carless and I head up the GDC events, including the IGF – and I’m CC-ing Brandon Boyer, the IGF chairman here.

Before you go ahead and do that, could we have a phonecall discussing your perception of what happened during judging and your impressions of what didn’t run correctly from your perspective? We _do_ actually care about individual entrants such as yourselves, and it upsets us when people don’t feel like we’re doing a good job. So let’s talk about it directly!

Myself and Brandon are available at a few times on Monday – I’m in U.S. pacific time and he’s on U.S. central time. Do you have time for a call?

Thanks,

Simon Carless

EVP, UBM TechWeb Game Network

We considered calling. At the very least, we decided not to post what we would have, and gave it some second thought. Let’s be honest: It is obvious that Brandon Boyer and friends care about the IGF as the prime outlet for indie games. We don’t doubt that. But this isn’t about handling the situation silently. If we had called and talked about our concerns, the heads of the IGF don’t have to be held accountable for a broken judging system. It’s about transparency, which is something the IGF completely lacks.

So there it is, our story about the IGF. We hope that, as a community, we can change the IGF for the better by exposing flaws in the judging system and holding those in power accountable. But until then, please hold off on marking the IGF as the be-all end-all of indie games. Instead, join protests like the IGF Pirate Kart. And if you’re still not convinced there’s something wrong with the IGF judging system, hear it from a judge herself.